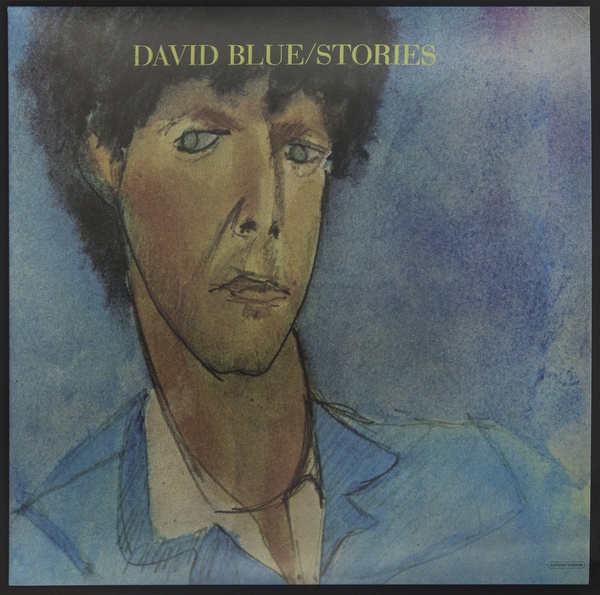

DAVID BLUEStories LPEREMITE (UNITED STATES)MTE 073LPRelease Date: September 30th 2022

DAVID BLUEStories LPEREMITE (UNITED STATES)MTE 073LPRelease Date: September 30th 2022 Backstage at the Roxy for Ronee Blakley's concert on August 18, 1976 in Los Angeles, California. Left to Right: David Blue, Lainie Kazan, Bob Dylan, Robert De Niro, Sally Kirkland, Ronee Blakley and Martine Getty.

Backstage at the Roxy for Ronee Blakley's concert on August 18, 1976 in Los Angeles, California. Left to Right: David Blue, Lainie Kazan, Bob Dylan, Robert De Niro, Sally Kirkland, Ronee Blakley and Martine Getty.David Blue is a difficult artist to get a handle on. He was a big, sweet-talking guy who drifted from Pawtucket, Rhode Island down to Greenwich Village in order to become an actor after being tossed out of the Merchant Marines in 1960. He got a gig washing dishes at the Gaslight Cafe, and began running with musicians more than actors, because that's where the action was. As testament to his bravura and personal magnetism, he soon became a confidante of pre-fame Bob Dylan and pretty much everyone else on the Village scene. Eventually he decided to try his hand at the musical side of things as well. He learned a lot about the guitar from the legendary underground hero Luke Faust (future Insect Trust member, also a sometime member of the Holy Modal Rounders), but he was always a keen observer, quick to see the essence of what was going down. Paul Rothchild chose him to put a few songs on Elektra's 1965 Singer Songwriter Project comp, which also featured the solo debuts of Bruce Murdoch, Patrick Sky and Richard Fariña. Performing under his birth name, David Cohen, Blue's tracks have a Tom Paxton-ish vibe, perhaps highlighted by “I Like to Sleep Late in the Morning,” which was subsequently covered by Tom Waits, David Bromberg and others as a good timey anthem.

Bob Dylan and David Blue, 1966. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Bob Dylan and David Blue, 1966. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesThe following year, Cohen adopted the soubriquet David Blue at the suggestion of Eric Anderson, since there were two other guitar-playing David Cohens on the scene. The name was based on the electric quality of Cohen's eyes. He ran the idea by a couple of pseudononymous friends — Bob “Dylan” Zimmerman and Elliott “Ramblin' Jack” Adnopoz. They told him to go for it, and he did. He had not been playing the clubs under his new name for long before Jac Holzman signed him to record his eponymous solo album. Using a band with bassist Harvey Brooks, guitarist Monte Dunn and keyboard guy Phil Harris (all of whom were involved with the concentric Dylanoid circles), David Blue has a semi-generic Highway 61 vibe, but also contains moments of original greatness. These were not appreciated by Holzman, who sat on the LP like an angry duck, moaning he'd only released the album to placate the Village elite. To tour in the wake of its release, Blue formed a band called American Patrol with bassist Jack O'Hara and guitarist Bob Rafkin. American Patrol toured the U.S. widely during '67, recording an unreleased LP for Elektra in this time. A worthwhile bootleg of a live gig at Boston's Unicorn Coffee House is floating around, but nothing else has emerged. Unsurprisingly, David Blue was not a hit.

In 1968 Blue signed with Reprise on the recommendation of his old pal, Phil Ochs, reportedly with the proviso that they buy and bury the American Patrol session. These 23 Days in September was produced by Gabe Mekler (best known for his work with Steppenwolf and Three Dog Fucking Night) and the Dylan vibe is dialed back a quite a bit (apart from Henry Diltz's cover photo). The instrumental sound is almost a folk rock take on NYC's baroque-pop moves of the moment, and Blue's vocals are flat enough to make me think of Randy Newman. Long a favorite with Japanese folk collectors, 23 Days offers a sparer sound than Blue's debut. There are also some good tunes on the album, eschewing the surrealism of Dylan for a more personal vision. But like its predecessor, 23 Days drowned like a cat in a bag the moment it was released.

David Blue, 1966. Billboard

David Blue, 1966. BillboardAround this time, Blue split New York for L.A. But not much was happening there, either, apart from regular breakfast meets with fellow ex-pat, Ochs. Blue had placed a few songs with other artists when he was still in Manhattan, but he wasn't getting much action in that department. But Blue was still signed to Reprise. For his second record for the label, Me, he decided to use his birth name and go to Nashville to record. The latter decision added some country twang to his vocal delivery and its musical setting. Paul Tannen produced the session (his first since Don Rickles' Hello, Dummy), and the band is uncredited, although it sounds like the Area Code 615 guys who had just played on Nashville Skyline. Recording fresh on the heels of a bad break-up, Blue's lyrics have some very dark passages, although these are undercut by the hillbilly accent he allows to infect his vocals. Some people love Me, but I find it so-so, and the name change was more confusing than liberating. He was dropped by Reprise in 1970.

By most accounts, Blue was a druggie from back in his early Village days. His interests in this area widened as his fortunes diminished. He maintained his status as a Lothario, however, and was picked up by David Geffen Management at the suggestion of Joni Mitchell. Joni had been a friend (and etc.) since 1966, when Blue, Eric Anderson, Tom Rush and various other touring folkies would crash at the fifth floor Detroit walk-up Mitchell shared with her then-husband, Chuck. By the early '70s, Joni was the queen of the SoCal scene, so her word carried a lot of weight. Geffen also signed Blue to his new label, Asylum. Blue's masterpiece, Stories, was the Asylum's third release, following Judee Sill and Jackson Browne.

Stories is a brilliant downer of a record. But like virtually all such albums on major labels (apart from Skip Spence's Oar) it has a high-end production quality that keeps things from becoming too cracked. Blue was reportedly in “a good place” when he did the session, so perhaps he's just inhabiting a loser's persona, but the whole album is as soaked in despair and confusion as Bob Desper's New Sounds, Dave Bixby's Ode to Quetzacotl or Dana Westover's Memorial (to Fear).

Stories is broken into two distinct musical halves. The a-side is mostly built around a pair of acoustic guitars (the second played by old American Patrol bandmate, Bob Rafkin), providing an excellent setting for Blue's new semi-spoken approach. He employs a vocal attack more aligned with those of Leonard Cohen or Kris Kristofferson, focusing on the same sort of intensely personal lyrics he'd explored on Me, while dropping the cornpone conceit.

Stories begins with “Looking for a Friend.” Lyrically, it resembles one of L. Cohen's observational mopes, until it gets to the chorus where the melody takes an upful turn and the words, “Looking for a friend/Looking for a good friend,” bathe the song in sheer naked pathos. This feeling continues, as Blue goes on to explain his quest. And the more you know of his personal story, the stranger it seems. This guy, after all, was part of the inner ring around Dylan in his pre-Woodstock days. Now he sounds like a man sitting on a bench outside the bus terminal in Hell, asking new arrivals if they'd like to be his pal. Perhaps he's just drawing upon memories of his youth (which sounds like it was pretty lousy), but the more often I hear this tune, the more fully broken it sounds.

The second song, “Sister Rose,” is in the same mode, although the references to Catholicism, snow storms and Montreal make the Cohen parallels feel more explicit. It's hard to tell on this one whether Blue is exploring his own experience or taking on Cohen's manner of allegorical writing the way some people take on accents. It's a bleak vision, but one that doesn't always register as absolutely authentic.

Third up is “Another One Like Me,” which feels much closer to the truth. Although, objectively, the lyrics could have been written by Harry Nilsson to be sung by Bluto to Olive Oyl in Robert Altman's Popeye, the brash sentiments of the song are something you can imagine Blue saying. Musically, the song is beautifully constructed. Ry Cooder's slide work is fantastic and the sustained organ line by Ralph Schukett (ex-Clear Light) is perfect, and the diametric opposite to his insanely bustling work on Carole King's “Raspberry Jam” a year earlier. But lyrically...man, talk about taking a last wild shot at turning shit into gold.

The side ends with “House of Changing Faces,” which is about going down the drain on a wave of heroin in San Francisco. The guitar (by Rafkin, I suppose) has a light Spanish lilt in spots, but the message is anything but light. “I still have the tracks to remind me/what life was like when I was wasted/and I wanted to die.” The chug of the rhythm guitar keeps things moving and against the huge static weight of the words, but the insect paranoia of the instrumental outro is a thing of weird and appropriate beauty.

Side Two offers a different approach to the songs. There are more instruments, more formal arrangements, and even some outright rock motion. The first song, “Marianne” is Blue's supreme ego-move on Stories. The song is basically a boast Blue makes that he slept with Leonard Cohen's muse, Marianne Ihlen. He makes a point of using the proper Norwegian pronunciation of her name, and it's set to the strains of a Quebecker accordion courtesy of Pete Jolly. It reminds me of something the singer Jennifer Warnes told Simon Spence in a recent issue of Mojo, about why Blue slept with Dylan's wife, Sara. “David was trying to find out if Sara was the reason Dylan was Dylan,” Warnes said. Perhaps he was hoping to discover what made Leonard tick as well. Either way, it seems like a crazy thing to write a song about. But Cohen remained one of Blue's fiercest partisans, getting him gigs in Montreal, recording his final sessions, introducing him to his eventual wife, Nesya.

For “Fire in the Morning” Blue switches from guitar to piano, and there's a nicely tense string arrangement from Jack Nitzsche. The song is another one about losing love and not being able to figure out how to deal with it. It's a simple notion, but one that Blue is able to frame in a million ways. For this effort his begging has a powerfully raw and poetic quality, but it remains hung up on a repeating dream that is impossible to fulfill. In the process it gushes like a lovely fountain of despair.

Next up is “Come on John,” another junkie song, throbbing with a full band rock pulse. The tune had already been recorded by Helen Reddy on her self-titled debut album, where it appeared comfortably amidst covers of Donovan, Lennon and Randy Newman. Here, the band sounds pretty good, but Blue's voice has a hard time matching this sort of material.

Stories ends with “The Blues (All Night Long)” which finds Blue on piano again, with great performances by Cooder, Schukett and Rita Coolidge (just beginning her break-out from the Leon Russell Circus). Blue's voice is back in its comfort zone, with lyrics that are resolutely beat. “I've destroyed what I love/Have been weak and strong/The end has come and gone/I have flown and have fallen/With angels and thieves/I have been broken/And broken free.” The words to the final song on Stories have hopeful moments, but they are scattered on a sea of despond.

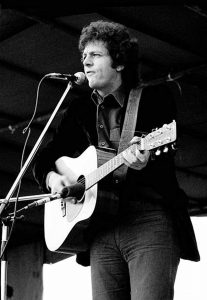

David performing at the Roskilde Folk Festival in Denmark, 1972. Jorden Angel/Getty Images

David performing at the Roskilde Folk Festival in Denmark, 1972. Jorden Angel/Getty ImagesThere's something magical about the way David Blue processes all this self-imposed destruction. With this album he manages to transmute his personal agony into truly transcendent art. When it was released, Stories sold about 2,000 copies. And Asylum actually tried to push the record! Blue toured with Jackson Browne. He got to play Europe for the first time. But he just couldn't catch a break.

Three more albums on Asylum followed, but they grew increasingly tame. His final LP, Cupid's Arrow, was released in 1976. He continued doing some music, and appeared for a while in Montreal doing a show playing Leonard Cohen songs while sitting in a fake tree (or so I've heard). But he eventually refocused on his acting. After parts in Dylan's Renaldo & Clara (where his ten-minute freeform rap at a pinball machine is a YouTube must-see) and Neil Young's Human Highway, Blue started getting real work offers, and moved back to New York with his wife in order to take advantage of them. Back in Manhattan he was also something of an eminence grise on the then-current folk scene and seemed to enjoy his status. He died of a heart attack in 1982 while jogging, at the age of 41.

The elegy Leonard Cohen presented at his funeral can be found on the internet, but I'll quote a short passage.

“David Blue was the peer of any singer in this country, and he knew it, and he coveted their audiences and their power, he claimed them as his rightful due. And when he could not have them, his disappointment became so dazzling, his greed assumed such purity, his appetite such honesty, and he stretched his arms so wide, that we were all able to recognize ourselves, and we fell in love with him.”

Stories is an amazing example of what David Blue was capable of. Dig it.

Backstage at the Starwood in Los Angeles, California, 1978. Leonard Cohen, David Blue (seated), Devo, and Martine Getty. Brad Elterman/Getty Images

Backstage at the Starwood in Los Angeles, California, 1978. Leonard Cohen, David Blue (seated), Devo, and Martine Getty. Brad Elterman/Getty Images