Click here to purchase Live in Forli, Italy 1982Another superb live Robbie Basho album, recorded during a short Italian tour in 1982, a year after his final non-posthumous LP was released, and a mere four years before his death at the hands of a chiropractor.

Like most dorks, I came to Basho's music through its relation to the work of John Fahey. Back in the quaint days of yore, I'm pretty sure we all assumed that anything with a Takoma label slapped on its side was something that Fahey had personally approved. Nobody I knew realized that ED Denson had been an equal partner in the label almost from the start, and that a fair number of the early artists signed to the label were brought aboard by ED, rather than by the titular captain of the Takoma Records steamboat. So it was with Basho.

Although Robbie (brought up under the name Daniel Robinson Jr.) was from Maryland, he was not part of the Takoma Park scene until its very end. Through Max Ochs, Basho had discovered the music Davy Graham would describe as “folk, blues and beyond.” Robbie appeared on stage, reading a Fahey script at the Episcopal Youth Show John organized at St. Michael's Church in March 1962, but that seems to have been his only recorded interaction with the proto-Takoma set. Not long after this Fahey split to Berkeley (hot on the trail of Pat Sullivan) to attend graduate school at the University of California.

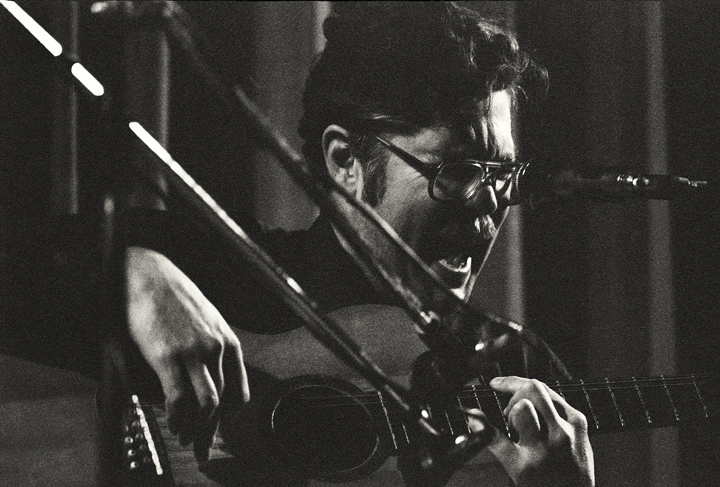

Photo Credit: Ron MayFor your amusement, here's a smattering of Fahey's ruminations on Basho, as recorded during an interview I conducted in Oregon in the '90s.

FAHEY: I knew Basho in Maryland, but he was just Robbie then. I think it took a few years in Berkeley for him to become Basho. I remember the first time I met him. I didn't like him. I was scared of him. I noticed he was solid muscle. It turned out his summer job was as a bouncer in Ocean City, Maryland — a tough place, too. He didn't get into Meher Baba until he got to the west coast.

There were about 30 or 40 people I knew who planned to move to Berkeley. And we all moved out there around the same time. But Basho wasn't in on it. He just followed us to Berkeley. He liked it there. He stayed 'til the end.

COLEY: You once mentioned that Robbie ate some hallucinogens and went up on a mountain top where he “received” the name Basho.

FAHEY: I don't know that he did that. He told me that he did that. And that's one reason I never did LSD. I might become King Kong. But Basho was screwed up to begin with. He was nasty. I couldn't stand the guy, couldn't take it.

COLEY: Did he and Denson get along?

FAHEY: I don't think they got along, but Denson thought Robbie had a wonderful voice and would sell millions. He also thought Charlie Nothing would sell. Denson was always motivated by money. I didn't have to be, because my grandfather was putting me through school.

COLEY: Was there any trouble with the second press of Basho's first album (Seal of the Blue Lotus) because of the swaztika on the cover?

FAHEY: Nobody complained about it as far as I know. But I was at UCLA. You've got to remember that Denson was in Berkeley running the company. When I bought the company back, or whatever I did, here were all these records by Basho. I knew who he was, but I didn't know that he'd made records. Denson was up there doing secret stuff with money, funneling it to Country Joe.

COLEY: How did you feel when you found out you had a label with four and a quarter Basho records on it?

FAHEY: It was like a bad dream [laughs]. No, I felt he had some value. I like those records, but it took a while to learn to like them. I really don't think that Falconer's Arm is very good. But I didn't know about it, honest. Denson was doing it.

COLEY: How could you be going up to Berkeley to play all the time and not see those records?

FAHEY: I just didn't. There were two big truckloads of records that came down to L.A. We had to carry them up to the second floor. When I started opening them I saw all these things for the first time. I freaked out and called Denson up and said, "What are all these Basho records?" "Oh, I thought he had a lot of talent." At some point I decided to keep him on and let him make a record every year, 'cause records didn't cost that much.

[Al] Wilson had been listening to him, and Wilson and I talked about everything in the world. He got me to listen to "Bardo Blues." And I listened to it a few times carefully, and it blew my mind. Even though the tape recorder runs out of tape in the middle of it, that's one hell of a piece de resistance. Then I liked the piece after it. But it took some encouragement from Wilson. Then "Dravidian Sunday" I like a lot, even though it's full of mistakes. So that's how I came to appreciate Basho.

The one I like the best is the whole second side of Song of the Stallion. I don't like the first side, but the second side works. All the way through. It's just beautiful, even his recitation. It gets corny in spots, but overall it's beautiful. Wilson described him as having moments of brilliance. I'd go a bit further than that and say that there are pieces that are brilliant all the way through. But most of it's sentimental drivel. He could never tell the difference between schmaltz and anything else. He couldn't tell.

Although I teased him unmercifully every time I saw him, I tried to treat Basho right, in terms of making records and paying royalties and giving him advances. He was always behind. He never made the company any money. He was an artist that we sort of sustained, one of the rationales being, well, people will notice that he's on the label and think that maybe they can get on the label.

But the main reason I never liked him was simply because of his manners. His attitude towards other people was just that they didn't exist. Robbie Basho existed, and nobody else. I saw him write notes to himself on 3X5 cards back in the '60s. One I remember is, “Be patient, Robbie. SHE is coming.” He must have been very patient. My impression was that he was terrified of girls. He was solid muscle, but such a pussy. Another thing about Basho — if you called him Basho, he'd turn and say “Bosho, please." He was probably the most fucked up guy I knew on the outside world.

COLEY: Did he actually walk around dressed like he is on the cover of Falconer's Arm?

FAHEY: He only dressed up for record covers. Or shows. But those must have been his own clothes, 'cause I saw him with those dumb things on several times. And those fruity boots! What kind of person wants to put those sorts of clothes on?

COLEY: He looks sort of stoned in that cover shot.

FAHEY: Well, by this time he was into his religious thing. And he'd built up his fingernails so they looked like gigantic claws.

COLEY: Was Basho a heavy doper at any point?

FAHEY: He did a lot of benzedrine for a couple of years. Then he stopped that. I thought he made more interesting records while he was on dope, myself. Those first two records and probably the singing record. That's a record that has a built-in defect on every copy, but we didn't notice it. It skips one groove.

COLEY: You told me a story about him doing a lecture at the Ash Grove.

FAHEY: Well, before he played at the Ash Grove he was going to stay with me and my wife in L.A. Of course I was teasing the hell out of him. He started talking about the evil accretions that were crawling all over the floor, getting thicker and thicker and higher and higher. He was saying that we'd all have to get out of there pretty soon or we'd all drown. So my wife went and got a vacuum cleaner and said, “Look, Robbie, they're all going into the vacuum cleaner.” He couldn't take a joke. So he left. He found some fellow Meher Baba-ite and went and stayed with him. That evening at the Ash Grove, for his first set, he gave like a 20 minute history of the guitar. All wrong!

COLEY: Did he give any samples of styles or anything?

FAHEY: No. It was just spoken and it was all fucked up. It was like, “American Indians are the same as Hindus,” and all that stuff. It wasn't even funny, it was so pitiful.

COLEY: He was the warrior of a lost tribe.

FAHEY: But he was the only one from the tribe. That was his trouble.

Nove, Italy in 1982. Photo Credit: Angelo Aldo FilippinRegardless, Basho cut five LPs for Takoma in the '60s, although the two volumes of Falconer's Arm were supposed to be the debut release of a label run by Moe Moskowitz, of Moe's Books fame, who had also financed Seal of the Blue Lotus. No idea why that didn't come about, but rumors were that Robbie had gotten on the wrong side of Moe's wife or something. Those five fundamental LPs — Blue Lotus, Grail & the Lotus, Basho Sings, Falconer's Arm I & II — were joined by Robbie's brilliant contribution to Takoma's Contemporary Guitar Spring 1967 LP, “The Thousand Incarnations of the Rose” (which has leant its name to both a compilation LP and a music festival).

These were followed by Venus in Cancer, a 1970 LP on Bob Krasnow's Blue Thumb label, which suffered from some odd production flourishes and truly hideous cover art, but contains some nice music. Better was its follow-up, Basho's last LP for Takoma, Song of the Stallion. After this came two LPs for Vanguard, 1972's Voice of the Eagle and 1974's Zarthus. A few years later, Basho acolyte, William Ackerman founded the Windham Hill label and released 1978's Vision of the Country and 1979's Art of Acoustic Steel String Guitar. These were followed in 1981 by Rainbow Thunder on Silver Label. After this, Basho's only releases during his life were cassettes with a meditative vibe.

Still Robbie recorded and played regularly through the years. But there was no audience for steel string guitar music in late '70s and '80s. While Basho has been hailed in some quarters as progenitor of the new age sound, I don't hear it. There just always seems to be a lot more meat on these strings than that genre permits. And his vocals are another thing entirely.

I remember the first time a friend and I saw the cover of Basho Sings. Churls that we were, we thought it was a joke. There was something so monumentally sentimental, earnest and humorously heroic about the way Basho sang, the very thought of an entire album dedicated to his vocalizing made us burst out of laughter. It took years of listening (and stern lectures by both Glenn Jones and Dan Ireton) to make me rethink this stance. While I would still be loath to play most Basho vocal turns for someone I didn't know very well, I have begun to view them as possessing a strange sonic quality that's pretty cool. The lyrics might still have a daffy Walter Mitty vibe, but what the hell?

But Robbie's guitar playing is really what you want to hear. His mature technique is based more on classical traditions than those of blues or folk, and the international range of influences you can pick up (either specifically or just vaguely) are amazing. Basho's deep trips through Hindu, Native American, Persian and other musical cultures all make themselves felt. And the cumulative effect is not quite like anything else. It's fortunate for we listeners that true believers like Glenn Jones held onto taped evidence of what passed so many others by. Meaning we now get a chance to reconnect with music like that on this LP. The song selection is typical for of Basho's late '70s/early '80s setlists, mixing tunes from various LPs with some new ones that never made it to the studio. And you get a sense of how charming Basho could be in polite company, and maybe how needy he was as well.

If you have not yet checked out Basho's recordings, this makes an excellent intro. He may have been a troubled individual, and probably not the greatest guy to hang out with, but that's all academic now. The recordings exist as his ghost. And in this sense, Robbie Basho is as friendly as Casper. No matter what Fahey thought.