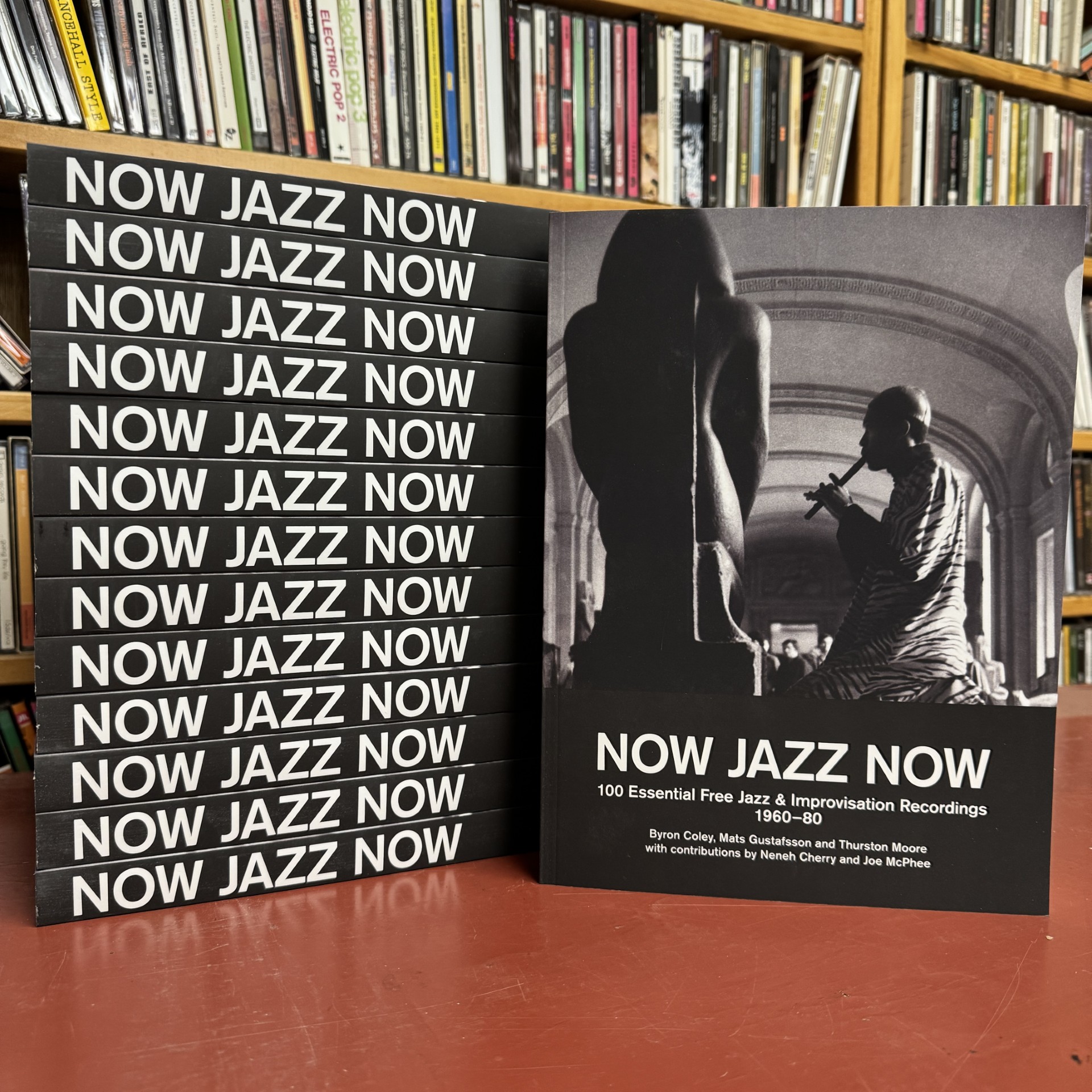

New book from ECSTATIC PEACE LIBRARY: Now Jazz Now: 100 Essential Free Jazz & Improvisation Recordings 1960-80 by Byron Coley, Mats Gustafsson, and Thurston Moore (9798993404004, 277 pages, 2025)The idea for Now Jazz Now was something Thurston and I began tossing around seriously in the waning decades of the 20th Century. It was a long time coming.

The process really began somewhere in the latter '80s when we were introduced to Bernard Stollman, the elusive honcho of ESP-Disk'. Bernard was in the process of retiring as one of NY State's assistant attorney generals. He approached Doug Wygal, who was doing A&R at Sony in NYC, with a plan. Bernard suggested that Sony purchase the rights to the ESP-Disk' catalog and start reissuing its music on CD. Doug was an old pal of ours from his days in the Lust/Unlust band, The Individuals. He reached out to me and Thurston because we were the only people he knew at the time who were seriously obsessed with collecting and documenting free jazz. Doug asked for advice, so we happily made contact with Stollman and eventually, we reported back to him that Stollman's documentation vis-a-vis the ESP master recordings was going to be problematic for Sony's legal department. That particular project was shelved.

Frank Wright and Noah Howard, Studio Pathe Marconi, Paris, 1970

Frank Wright and Noah Howard, Studio Pathe Marconi, Paris, 1970But Bernard and Flavia Stollman (his wife? ex-wife? her status would change depending on the day) became people we would see regularly, since we decided to start working together on a book documenting the story of ESP-Disk' and all its squirrely machinations. Flavia was legally blind and we had some very nutty meetings with the pair at a now-closed cafe on Tinker Street in Woodstock, NY. Bernard, always playing the angles, would have locally-based musicians (like Paul McMahon) “just happen” to fall by while we were there, usually to pitch the idea of getting an opening slot for Sonic Youth. It was a weird game, but Bernard was such a pleasantly odd duck, and so jam packed with bizarre anecdotes and factoids about the '60s underground in NYC, we could never turn down an invite to visit. Although, truthfully, we were often more interested in getting a chance to hit Woodstock's Blue Mountain Books, which we'd discovered was the store where Dick Higgins (of Something Else Press) sold off piles of amazing concrete poetry and all manner of oddments.

During these meet-ups Bernard tried to rope us into writing his biography as part of an authorized book on the label. He passed along a bunch of essays he wrote about various musicians with whom he'd been involved. These were fine, but the fact he'd licensed a bunch of records to the Italian Base label in the early '80s, without paying royalties to any musicians, meant his name was Mudd in the NYC music scene. Bernard was not keen on us running a parallel narrative not of his own design, so we pulled back from doing that book. Just as well, since Stollman soon licensed ESP-Disk’ material to the German ZYX label, generating another well-deserved round of apoplexy in the avant jazz community. He eventually got Jason Weiss to do the book he'd envisioned — Always in Trouble (Wesleyan University Press, 2012). At that point we also tried to figure out if there was a way for Sonic Youth's label, DGC, to take over ESP-Disk', clean up the royalty situation and repackage the extant material (along with archival stuff), but after trying to unravel the knot for about a year we gave up on the notion.

This was an era where record stores were full of amazing, as-yet-unheralded LPs, many of which were still available from NMDS, Rick Ballard or North Country distributors. I remember taking Edwin Pouncey for a trip out to the Bay Area during which I scored a few hundred low-cost duplicates, and he was able to lay the foundation for a solid avant jazz collection for very little coin. The CD reissue era was beginning to pull the cloak of mystery off of a lot of obscure records by this point, but the internet was still clunky, eBay and Discogs were years away, and it was still possible to buy original Saturn LPs for under $10 at any college town in which the Arkestra had played a gig. So, these were good times, but hard information about free jazz was still difficult to come by, apart from some excellent — if obscure — discography books.

At the same we were haunting stores for old jazz magazines like Sounds & Fury, the original iteration of the French magazine, Actuel, and whatever else was around. Pickings were slim, but there were cool things out there, and the jazz library at Thurston's pad kept expanding. But we also both became parents in the '90s, so that put a bit of a damper on things. Thurston did manage to put together that “Top Ten Free Jazz Underground” list for the Beastie Boys' Grand Royal 'zine in '95, causing enough stir that we started reviving the idea of doing a book, perhaps label based, covering the artists on ESP, BYG, FMP, and so on. A couple years after that Matt Robin from the UK Charly label contacted Thurston about compiling and annotating a 3CD compilation (later issued as 6LP box on Get Back) they wanted to use to launch their BYG reissue series. We jumped on the chance and putting that together really fired up the idea of doing a book to help people explore the music.

.jpg) Free jazz musicians Pharoah Sanders, left, and Sonny Sharrock in Berlin, 1968, by © Philippe Gras, courtesy of Suong Gras from Now Jazz Now: 100 Essential Free Jazz and Improvisation Recordings 1960-80 (Ecstatic Peace Library).

Free jazz musicians Pharoah Sanders, left, and Sonny Sharrock in Berlin, 1968, by © Philippe Gras, courtesy of Suong Gras from Now Jazz Now: 100 Essential Free Jazz and Improvisation Recordings 1960-80 (Ecstatic Peace Library).Around the same time Thurston became friends with a Swedish sax player and record maniac named Mats Gustafsson. Together with Jim O'Rourke, the three would hit record stores around the globe and literally tear them apart looking for free jazz and whatnot. They even formed a band called Diskaholics Anonymous Trio, and made an album that was only available in trade for rare jazz. Mats was totally insane for records, and had a very solid grounding of both jazz history as well as the evolution of the international avant threads. From that point onward when we would talk about “The Book,” it was always as a three-person project. And when any of us got together we'd talk about it a lot, sharing information on whatever odd gems or stores we'd happened to discover in the wild.

This went on for years, and talking heavy records with people who actually know the stuff is bracing as hell. But we were all super busy with various things and could never really set aside the time required to do the project justice. Then, one day COVID hit town. Everyone's work schedules dissolved overnight. We took this as a message to get started on the thing, and began working out the details.

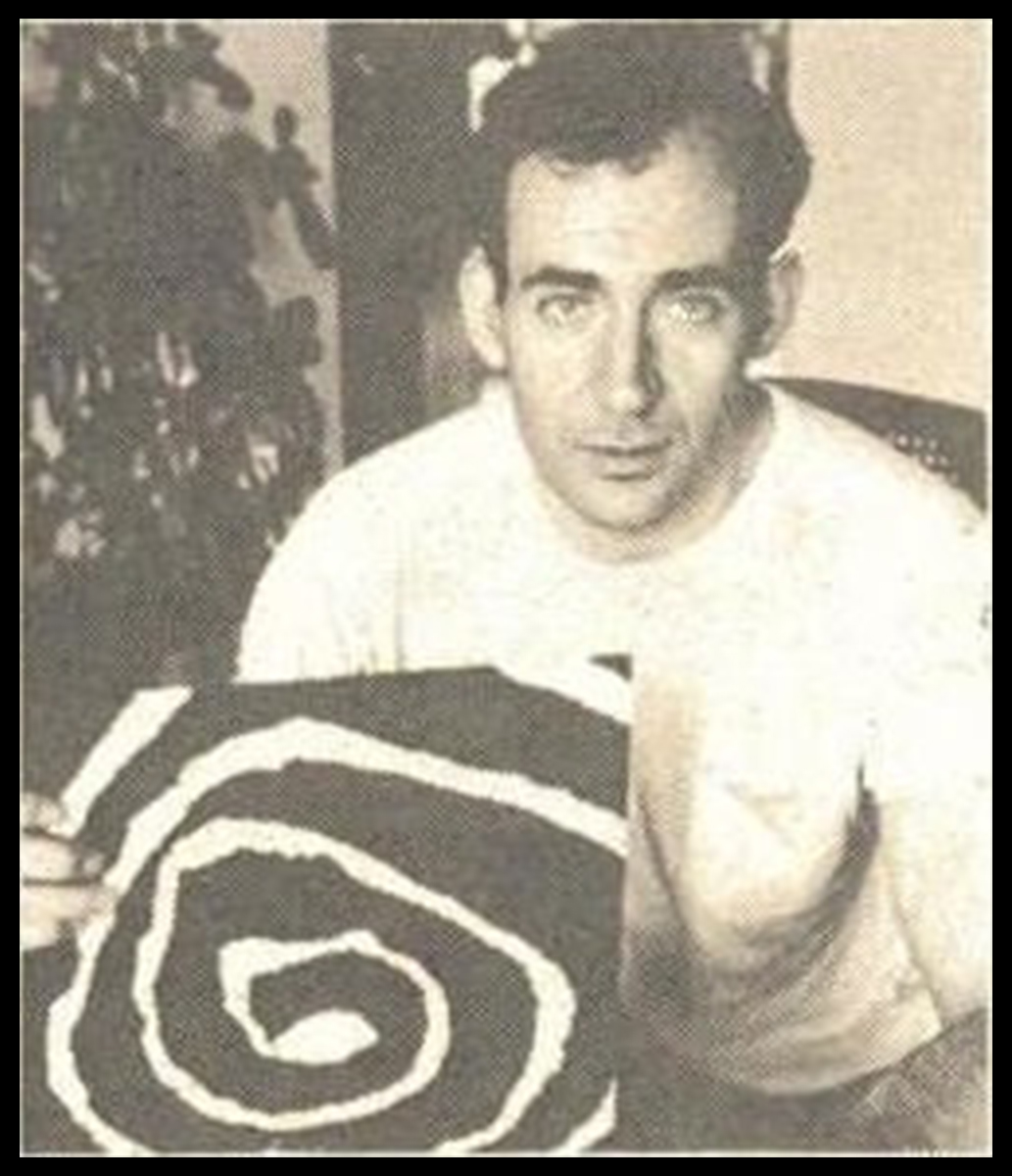

Bernard Stollman, founder of ESP-Disk. Courtesy of ESP-Disk

Bernard Stollman, founder of ESP-Disk. Courtesy of ESP-DiskFirst thing was to define what years would be covered. The heaviest years for free jazz action were probably ‘65-74 or so, but that was too small of a window to actually contextualize the music's flow. Mats was of the mind that 1960 was the year where the first real (non-anomalous) free jazz session took place, and he sent audio samples to prove it. We chose 1980 as the end point for a few reasons. It assured none of the recordings were ones that any of us had an actual hand in, it predated the CD era, and it was a span of time that would allow us to explore how the music's influence spread around the world. Admittedly, there were a few drawbacks by ending in 1980. Many countries did not have any real free jazz recordings released in that period, there was a paucity of female session leaders during those years, and there were a lot of active players who didn't actually get recordings out until later. But eventually we all agreed it was a two-decade stretch of important music that we could help highlight. And that would be enough.

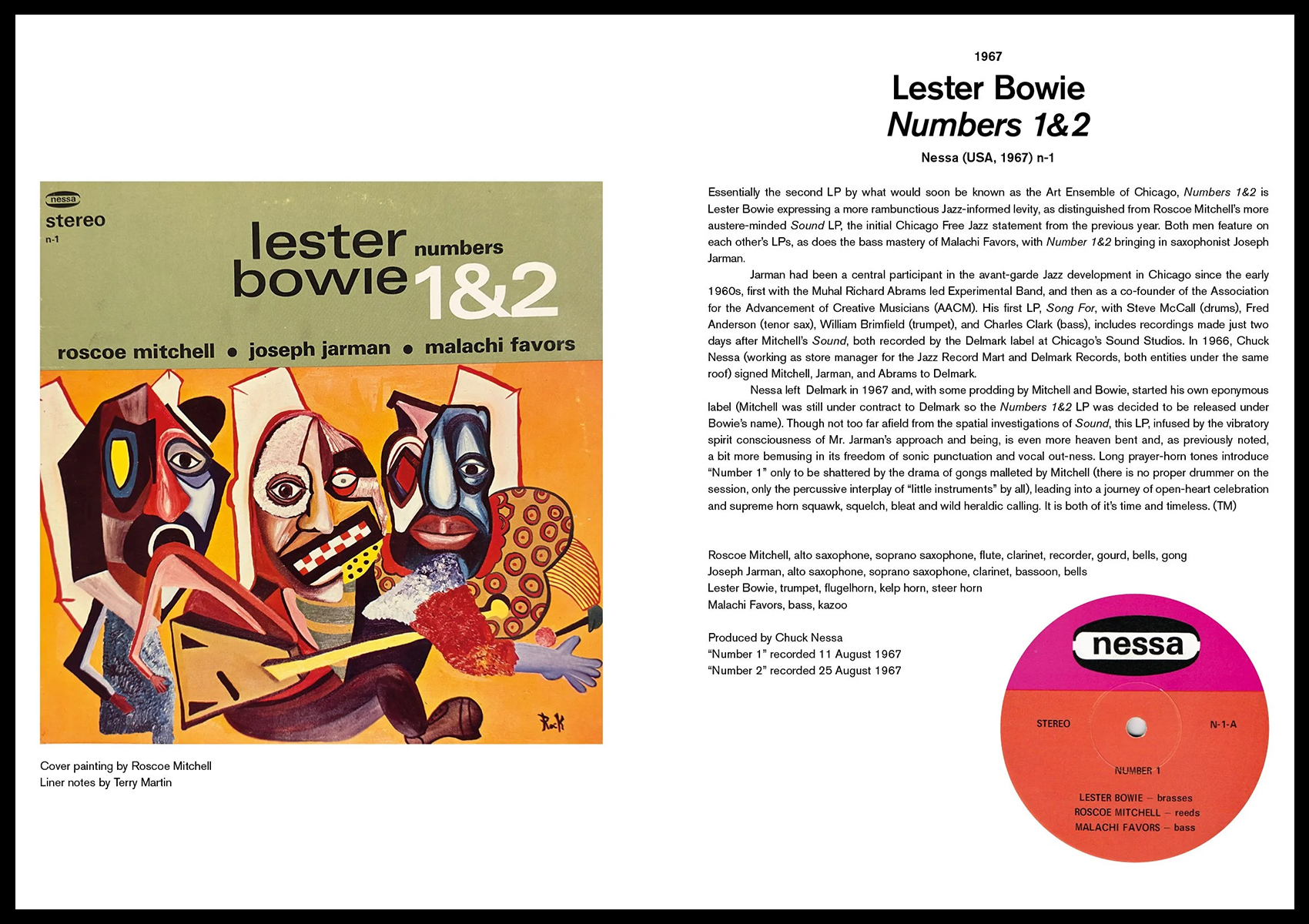

The next big question was what to include. This meant just pulling and playing thousands of records over the next few years. We each made a list of artists we hoped to explore and started going through records. Some artists like Cecil Taylor, Steve Lacy, and Sun Ra had a lot of goddamn records out, but we pretty much had them all, so it was just a matter of going through the stacks, taking notes and exchanging daily emails about our findings. In the course of doing this, we came up with additional “rules” for inclusion — no spiritual jazz (a nebulous term, I agree, but you know it when you hear it), choices based on release date rather than recording date (allowing us to trace how far-flung musicians were influenced by recordings rather than live shows), and not more than one release per artist as a leader.

For me this meant I'd head over to work and generally study 5-10 albums a day. The results were interesting. Records I'd recalled as blazing turned out to be more in a post-bop mode than anything free. And more than a few artists played very differently when a session was done under their name. Especially notable in this category was Pharoah Sanders — a wild free saxophonist as a sideman, but much more form and groove oriented as a leader. Others, like Sun Ra (whose name would be near the top on any list of important free jazz musicians), actually had almost no truly free sessions in their discography. And some, like Cecil Taylor, had a dozen ferocious albums worthy of any list.

We argued back and forth about details on these topics, and slowly winnowed the list down to 101 titles. There were no virtual fistfights, although opinions certainly varied, especially when the leader was prolific. Mats would also have to send us occasional sound files when he'd casually drop the name of some record Thurston and I had never even heard of.

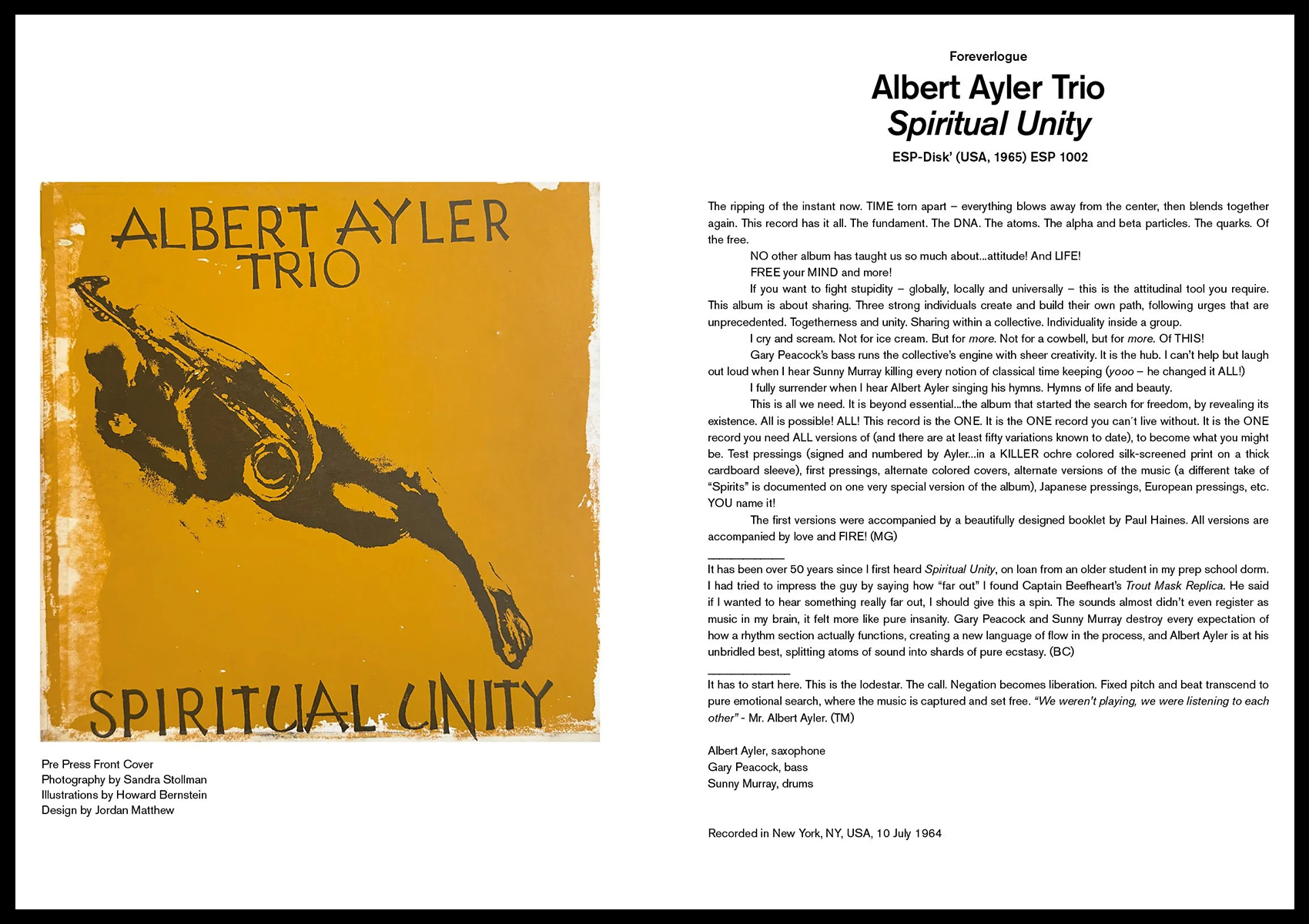

We had agreed, early on, that Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity was untouchable as a template for what free jazz could be, but everything else was up for discussion. Once we realized there were enough potential titles to do the list several times over, we began seriously taking into account geographical distribution and how individual records fit into the development and dissemination of the music. Finally, we divvied the records up into three batches and wrote them up, with as much context as we felt like adding. The three writing voices here are distinct, but complementary. And we were all happy to actually get the motherfucker done (thanks in large part to the editorial and design work of Eva Moore at Ecstatic Peace Library).

As with any such list, a lot of our choices can be argued with. We didn't feel bound by the stricture that all the music be entirely “free,” although much of it is. We tried to hit as many key artists as possible, but the choices are surely as much emotional as empirical. We all had records that were chosen for reasons of the personal impact they had, which is not always easy to define or defend, but what the hey. NOW JAZZ NOW is a book that can be read in small bites or huge gulps. It's basically just three guys who really like records trying to make a case for their collective obsessions.

Hope you can dig it.

—Byron Coley